In September 2020, Tim Kendall, a former Facebook Director of Monetization, stated that Facebook “took a page from Big Tobacco’s playbook” by making Facebook addictive. Sean Parker, a former Facebook president, has claimed that Facebook was designed to exploit a vulnerability in human psychology. Aza Raskin has apologized for inventing infinite scroll, and describes social media as “behavioral cocaine”.

Addictive substances: tobacco, caffeine, and alcohol have been with us for a long time. But the mechanisms of these substances are shrouded in chemistry. The nice thing about ‘behavioral cocaine’ is we can more or less see how it works. And this will help us to understand some of the most important problems about the position, called desire satisfaction theory, that what is good for you is just getting what you want.

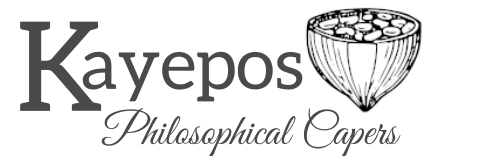

Desire Satisfaction Theory

I recently wrote about how philosophy’s uselessness is an indication of its value. Cameron Brow of the Brow Newsletter wrote an interesting and thoughtful response. I can’t reply to everything worthwhile Brow said in his post, but I do want to respond to one of his ideas:

” I can think of a number of people who would be (or who are) perfectly content living in a false reality with no access to philosophical truth whatsoever, as long as it leads to apparently pleasant outcomes. Such people cannot be said to follow (or exclude) the “wrong” highest good, because the highest good is determined subjectively by a person’s willingness to pursue it.”

That is, if you are willing to pursue it (or desire it), then it is good for you, and whatever you most desire is your highest good—the thing that is better than everything else.

Brow’s position seems to be a version of actual desire satisfaction theory: the view that whatever you really do desire right now is good for you. We should contrast this with ideal desire satisfaction theory, where what you would desire, if you were fully informed, is good for you.

An example will help to see the difference. We may desire to be in a relationship with someone we have a crush on, such as Ryan Gosling. According to actual desire satisfaction theory, it would be good for us to have this relationship. This will be true even if once we get to know Ryan, we discover that we don’t actually have much in common, and the relationship is unsatisfying. As long as we want to be in the relationship, actual desire satisfaction theory will say that it is good for us.

According to ideal desire satisfaction theory, the relationship is only good for us if we would want it even knowing everything about the person and the relationship: if, once we get to know Ryan better, we don’t want to be in a relationship with him, Ideal Desire Satisfaction Theorists will say that the relationship is not good for us. I’m not saying one or the other view is correct: some people prefer actual desire satisfaction theory, some people prefer ideal desire satisfaction theory. This example should help you see which theory you prefer.

Desire satisfaction theory has many things we want from a theory of the good. It explains why we should care about what’s good for us: after all, what’s good for us is just what we want. It makes the good a question of things we can observe, measure, and study scientifically, instead of having to rely on methods such as studying the human function (Aristotle’s approach), imagining almost-empty universes (G.E Moore’s), or designing ideally repressive cities as analogies to the human soul (Plato’s approach).

More significantly, desire satisfaction theory allows people to define the good for themselves. If Elon Musk feels another hundred billion dollars will make a tangible difference to his well-being, then who am I to say that this sounds unlikely? If he wants it, he wants it. If a child wants to run away and join the circus instead of becoming an accountant, then a desire satisfaction theorist will affirm the validity of the child’s desire. Different people pursue different things in life, and that’s OK: we want a theory that can help us recognize that people can want different things.

The Addiction Objection

Addiction has long been used as an objection against forms of the desire satisfaction theory. Derek Parfit raises it in his seminal work on ethics, Reasons and Persons:

I shall inject you with an addictive drug. From now on, you will wake each morning with an extremely strong desire to have another injection of this drug. Having this desire will be in itself neither pleasant nor painful, but if the desire is not fulfilled within an hour it would then become extremely painful. This is no cause for concern, since I shall give you ample supplies of this drug. Every morning, you will be able at once to fulfill this desire. The injection, and its after-effects, would also be neither pleasant nor painful. You will spend the rest of your days as you do now. (Reasons and Persons, p. 497)

This desire will, of course, bring with it some inconvenience. You will have to have an injection, you will need to carry supplies with you, and so on. In a philosophical thought experiment, however, we can assume what we want. So, we will just assume that the desire for the drug is much stronger than our desire to avoid the inconvenience. We will now have an extra desire, for that sweet injection in the morning, and it will be satisfied every morning. Parfit argues that this does not make our life go better. But according to Desire Satisfaction Theory, my life should be going better.

Desire Satisfaction Theorists can respond by saying that only some of your desires count towards your happiness. Parfit suggests that we should only count global desires: desires about how you want part of your life, or your whole life, to go. Because overall I would prefer not to be addicted, on ‘global desire satisfaction theory’, it will not be good for me to be addicted.

If you want to learn more about cool philosophical theories, check out our courses

A more recent suggestion, from Chris Heathwood, is that we should only count desires where we are ‘genuinely attracted’ to the object, rather than behavioral desires. Desires where we are genuinely attracted to the object are desires where we tend to view the object with “pleasure and gusto”. Behavioral desires are simply dispositions or tendencies to choose one thing over another.

Heathwood points out that Parfit’s case does not involve being genuinely attracted to the injection: the person seems to view it with indifference. It seems to be a merely behavioral desire. If the person were genuinely attracted, Heathwood argues, then the case would be very much akin to introducing someone to a new hobby they loved, which would be an improvement to their life. (p. 678) Heathwood rightly points out that Parfit’s addiction case lacks many of the features typical of addiction. In particular, the medical definition of addiction includes an impact on other parts of one’s life such as work, relationships, and health: Parfit’s ‘addict’ has none of these consequences.

Engineering Desires

What I love about Parfit’s addiction case is that it highlights the mechanisms by which desires can change. We are familiar with the fact that our desires can change through injections, smoking, eating and drinking. We do not generally think that such changes in our desires change what is good for us, but rather, that they can either benefit us or harm us. Taking anti-depressants might restore our interests in life, seeing our friends, getting exercise, and reading, and we see this as advantageous; drinking alcohol might make us want to drink excessively, and we see this as disadvantageous. In these cases, we think substances can improve or distort the alignment between desire and what is good for us.

But we may think that addiction is an exceptional case, and that we usually want things that are good for us. The addiction examples are interesting, but desire satisfaction theory was not really talking about these cases. They were talking about ‘normal’ desires. This is what thinking about our desires for social media adds. It gives us an insight into the sort of mechanisms that normally shape our desires, and how fluid, fragile, and capricious our desires are.

I’m not talking about full-blown social media addiction here. Social media addiction can interfere with the rest of our lives, taking our time away from our families, sleep and taking care of our bodies through exercise. This is important, but, like our substance abuse cases, are cases of desire gone wrong. Rather, I want to just focus on how social media creates and alters desires in a very ordinary way.

Now, I don’t want you think I don’t like social media. Social media is great. There’s a lot of value in it. It allows us to easily share updates about our lives, our thoughts, feelings and ideas with each other. It can help us to meet like-minded friends, and to staying in touch with distant ones, or when we are working long hours, or when we are in lockdown.

However, social media apps make us want to be on them, and they do this without increasing our connectedness, or the real value of the apps. The mechanisms they use are things which, on reflection, we would see as rather trivial.

One of these mechanisms is infinite scroll: the experience where you never come to the end of your timeline. Whether a social media app uses infinite scroll or not makes no difference to its value in our lives in terms of connectivity (except perhaps negatively), but it makes us want to use the app more. Moreover, our desire to use the app will often be accompanied with plenty of gusto: it is a genuine attraction. Now, maybe you think that having infinite scroll on twitter somehow makes your life better. That’s fine. But it would be nice to know how you can argue for this without presupposing that desire satisfaction theory is correct.

We can say similar things about the like button. Receiving a like on FB from somebody you haven’t spoken to since high-school is not increasing your connectedness with others in any meaningful way. However, FB likes give us a hit of a brain chemical known as dopamine: after we receive this, we want more. The like button on FB therefore also increases desire to be on FB, without really increasing the value of the platform. What it does do, however, is benefit FB: if we spend more time on FB, we will consume more ads. Showing us content that makes us angry is similar: we want, often with great gusto, to tell other users exactly what we think of them and their stupid fake news. But on calm reflection, most of us realize that this is a total waste of time.

What the like button really shows, I think, is how much our desires are just shaped by other people’s approval. The like button is like someone smiling at us, or telling us we have done a great job. But it’s clear that people’s approval is capricious, and so if your desires are linked to approval, they are also capricious.

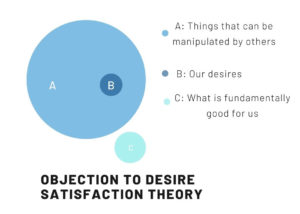

Significantly, social media reflects how our desires can be manipulated by other people to an alarming extent. This observation should make us reluctant to identify the good with our desires. For we do not usually think that what is good for us can be manipulated by other people for their own purposes. To set the argument out:

- Our desires can be manipulated by other people to their own end.

- What is fundamentally good for us cannot be manipulated by other people to their own end.

Therefore - Our desires and what is good for us are two different things.

There is, of course, a sense in which premise two is false. People can threaten us with punishments and offer us rewards for doing things for them: this is, in a sense, manipulating what is good for us. However, this involves altering the availability of what is good. Premise 2 concerns altering the nature of what is good for us. This is not open to manipulation in the same way.

What about global desire satisfaction theory? After all, most of us don’t have global desires to spend large parts of our life on social media. Perhaps global desire satisfaction theory gives us the right answer? The problem here is that our global desires, such as for the kind of career or body we want, seem to be shaped in much the same way as our other desires. Consider the way the fashion industry influences how much people desire to look a certain way. If this is the case, then our global desires will also be open to manipulation, and desire satisfaction theory will be false.

Coda: Desire Satisfaction Theory and Pluralism

Are we, then, to go around telling people they shouldn’t desire what they do and must conform to our view of what the good is? I want here to point out that there is an alternative. To keep this post from being monstrously long, I will just introduce the ideas here.

Value pluralism is the idea that there are multiple highest goods we can pursue. These may, for example, include knowledge, beauty, love, pleasure, connecting with nature, and sporting excellence. One theory is that they are developments of our positive human capacities. This allows space for open-mindedness and tolerance, while allowing us the theoretical tools to critique the manipulation of desire.

And perhaps the error we wanted to avoid was never thinking some ways of spending our time are just better for us than others. Rather, it was the dismissal of other worthwhile projects at the expense of our own. Aristotle and Plato thought philosophy was the highest good, rather than one good among many; no doubt athletes think sporting excellence is the best, and activists believe political achievements to be the highest goals. There’s room enough to claim that all of these things are good, without adopting the view that it is good for you to get whatever you want.